The NRA polarizes people. Some assume the worst from the NRA and others assume that the NRA speaks near-100% truth. Admittedly, I have been in the first group more often than not. Therefore, I made a conscious effort to watch the entire Press Conference the NRA conducted today concerning the outcry for gun control laws in the wake of the recent Elementary School tragedy. I have to confront my own prejudices like everyone.

Executive Vice President Wayne LaPierre spoke about our practices of placing armed guards at banks, sporting stadiums, around national buildings, around important people and then questioned why we do not do the same for children. He pointed to the problems of violent movie and video game content and music videos. He criticized the media for their unwillingness to report about this content. He criticized politicians for their unwillingness to take what he called the “hard stands.”

In the solution section of his speech, He called for congress to make the resources available to put an armed police officer in every school. Further, he pledged the NRA’s commitment to providing expertise and training. He indicated the need to look at access control, building design and adequate training. Finally, he introduced former US Congressman Asa Hutchinson as the NRA’s National Director of the National Shield Our Schools program.

Since you can read his comments verbatim, I will not try to summarize anymore. There are places where I agree with Mr. LaPierre. I have seen first hand the significant good that campus-based police officers do. They offer much more than security. Like everyone else, I wish that our police were better funded and that we could provide a police officer for every school down to the elementary schools. Second, I agree with him that gun control laws become the point of focus too quickly and too easily.

We do disagree. And in saying I disagree with him I want to also admit that I am guilty of making similar mistakes in different directions. All men are sons of Adam and brothers of Cain. Adam uttered the first lame excuse of human history by blaming someone else for his sin. His son Cain uttered the second lame excuse of human history implying he didn’t have the responsibility to be his brother’s keeper. Both of those tactics show up in the discourse around gun violence discussion along with other issues. So, by pointing these out in LaPierre’s speech I would simultaneously confess to them in my own.

LaPierre is right when he says that the NRA too easily becomes the target of the blaming. Yet, he too gives in to that temptation by blaming a host of others-media, politicians, makers of violent video games. Others, I agree with him, who share some of the responsibility for the problem. I think I would have found him more persuasive if he had admitted that the NRA has contributed to the problem. If he had admitted that the easy availability of guns, which the NRA has protected, is one among many contributing factors to gun violence, I would have found him persuasive.

The biggest disagreement I have with him concerns whether or not we are responsibility for our brothers’ and sisters’ welfare. His speech had an undercurrent, fatalistic anthropology. He repeatedly used the words “monsters” and “bad guys” as though we simply have to consign ourselves to live in world where people choose to do bad things because they are hopelessly bad people. I believe that there are some people who become hopelessly bad. And when that happens, I believe we all share part of the blame.

I believe that we help form one another. And should not consign ourselves to the inevitability of evil buy actively seek to counteract it.

We belong in a system of responsibility for one another. He said, “The only thing that stops a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun.” I cannot concur that the only way to respond to the potential for violence is armed protection against it. We should set aside the histrionics about whether we want an armed police officer responding should someone be breaking into our house. Armed protection is necessary. But just as the NRA claims that laws are insufficient so too I would say that armed protection is insufficient. It takes the transformation of hearts and minds, the development of habits of wholeness, and in a single word it takes conversion. When we admit that we ourselves have sinned because we are sinners and we make a conscious decision to turn from sin and turn toward God, we contribute to the conversion of our system. When service and witness together enable others to make that same move, we help repair our system. A good guy with a gun is necessary to stop some bad guys with guns. But the real answer is for the bad guy to enter a redemptive relationship with a good God.

There’s an analogy that the Baptist preacher and founder of Koinonia Farms, Clarence Jordan, used in talking about the impact Christ has on people. He talked about a mean dog. What the law does is chain the mean dog to a tree (he was talking about Old Testament law). What Christ does is actually change the nature of the dog. Similarly, in issues like this I think we have to come to agreement that laws by themselves are incapable of making the necessary changes. People’s violent natures must be changed. And that’s a transformation of the heart.

Friday, December 21, 2012

Thursday, December 20, 2012

Thursday, October 18, 2012

Election Day Communion Service

Election Day Communion began as an initiative among a couple of Mennonite pastors and and Episcopal Priest. While Citizenship tends to bring out the best in us, politics tends to bring out the worst. For Christians, Christ animates the former and forgives/reforms the latter. Election Day Communion is a day to come to the Lord's Table and in self-examination place before God the temptations of self-interest and judgmentalism and combativeness that we may have let get the best of us during the election season. It is a day to Remember God's grace through Jesus Christ.

Another name for Communion is Eucharist which means Thanksgiving. Election Day Communion is also a day to give thanks for the nation's freedoms, our citizens' character, and our shared commitment to community.

Thursday, September 20, 2012

Sunday, September 02, 2012

Concluding Thoughts on Extemporaneous Preaching

At the beginning of the summer, I launched on a project to utilize extemporaneous method of sermon preparation and delivery. This is where I compose an outline of the sermon and do not compose an entire manuscript. I had thought I would update the blog more regularly than I have but, there really wasn't that much to say. As we've reached Labor Day Weekend, I've decided the experiment is over. Here are my conclusions.

- Pastors who preach each week really should learn to preach from an outline at least occasionally. We all encounter weeks when time constraints prevent us from composing a manuscript. Too often, I have sacrificed exegetical and spiritual reflection in order to make time for manuscript composition. If I had trusted my extemporaneous abilities, I would have devoted the time I did devote to composing a manuscript to actually preparing content.

- For me, preaching with minimal notes really is better than preaching from a manuscript. When I preach from a manuscript, my eye contact is poor, my delivery is stiffer, I have frequent head bobs (looking down at script, looking up at congregation). Even when I have written a manuscript, generally if I run through the manuscript two or three times before Sunday morning services, I can preach with minimal or no notes.

- ALWAYS COMPOSE THE OUTLINE! I have used three methods of preaching--manuscript, extemporaneous (working from an outline), and memorized. Often when I composed a manuscript, I would simply begin writing without thinking through the entire structure of the sermon. That's not bad per se but it is what I would call free-writing--a helpful preliminary exercise but, not the best route to final form. Sermons do not have to be Point 1, Point 2, Point 3 sermons in order for preachers to think through the structure (often called form by the homileticians). Thinking through the sequence of ideas and also which ideas need the greatest attention happens best when I work from an outline. Sometimes, the idea needing the greatest explanation will come later in the sermon. When I outline, I am able to discern that and if I choose to compose an entire manuscript I can isolate that important idea and expand it as much as needed. Too often, when I write sermon manuscripts from beginning to conclusion, I can tell I'm running out of time or space in the manuscript and actually shortchange what should receive the greatest attention. I should have been practicing this all along but biggest learning from this experiment is ALWAYS COMPOSE THE OUTLINE. After that, I can decide whether to rely on the outline alone or complete the manuscript but the outline itself is essential.

- Writing is a way of thinking. Speaking is a way of thinking. Writing a sermon manuscript should not be abandoned any more than preaching extemporaneously should be neglected. Both skills are ways of accessing and reflecting on the text. For this morning's sermon, I wrote a manuscript for the first time in three months and found that some of the best insights came as I worked at composing each sentence.

- The keys to good extemporaneous preaching are humility and confidence. Humility to say to yourself--you're not really that good a writer. Confidence to say--you're not really that bad at talking simply and directly.

- The biggest area of weakness for me when working from an outline (extemporaneous) is the transition from one point to the next. I also know that my writing suffers from the same problem. One of my seminary professors once wrote about a paper that I had several good pearls but no string connecting them. That is too often the case when I'm preaching extemporaneously. Frequently, I end up treating each point as a discrete idea (mini-sermon) rather than thinking through and verbalizing the thematic thread that connects them. Thinking through and in some cases actually writing the introduction, the transitions, and the conclusion so that the sermon has coherence is an important step in the process.

Friday, August 24, 2012

Reflections after Reading Jeremiah 1-30

The decline of the church has been a topic of conversation for several years among scholars and writers who discuss these matters. Diana Butler Bass a church historian who has become one of the more helpful commentators on contemporary Christianity . Diana Butler Bass writes and reports extensively about this decline. Part of the evidence she cites is that 1 in 10 Americans considers themselves "ex-Catholic" according to 2008 Pew Research and only a quarter of the population attends a worship service in a "typical week." Her assessment is both honest and hopeful. She said in a recent TCU Ministers' Week Lecture, "System fail does not mean Gospel fail."

Richard Douthat in his much discussed article for the New York Times entitled, "Can Liberal Christianity Be Saved?" identified the Episcopal Church's liberalism as the reason for its decline. Douthat argument rests on two assumptions. Assumption 1--the Liberal trends were made to appeal to people. He wrote "Yet instead of attracting a younger, more open-minded demographic with these changes, the Episcopal Church’s dying has proceeded apace." Assumption 2--the conservative retrieval or return to traditional Christian configurations is the answer.

Both writers maintain description of the church and it's position in the world in terms of a left/right, progressive/conservative, liberal/orthodox dichotomy. Forecasters often identify the demise of the church and it's potential for recover, reformation or revolution in the church's capacity to respond to new needs and expectations of people. Yet, I wonder how the issues might look if we spoke of our situation in terms of a portion of biblical narrative rather than the categories available to us through culture.

I have recently been working my way through Jeremiah and I am frequently reminded of these discussions and others as I listen to Jeremiah's words to an exiled Judah. No, our exile did not come out of a violent experience of culture. No, we have not been physically displaced. We cannot compare the severity of our growing displacement with the oppression experienced by the 6th Century BC Jews. At the same time, because we lack these salient confrontations with reality, we also may not see clearly what is taking place. We are like the exiles in that increasingly we find ourselves at the margins of the culture.

Increasingly Christian faith enters the American public as a stranger in a strange land What lessons might we learn about living faithfully in exile? First, we can accept the changing situation as a context for readdressing the level of your faithfulness. In the early portions of Jeremiah, the Babylonian captivity is understood as God's act to bring about the repentance of the people. Even going as far as declaring the Nebuchadnezzar is God's servant (Jeremiah 27:6). Today, we might not believe that God orders national affairs in order to discipline and chastise God's people (maybe some people do, I don't). Regardless, learning to see our situation through this biblical narrative means asking questions about the nature of our faithfulness in the midst of this changing situation.

A second recurring theme in Jeremiah that I find both instructive and challenging is Jeremiah's confrontation of prophets who give answers that sound good but are in fact not from God. One particularly poignant example occurs in Jeremiah 28 where the prophet Jeremiah confronts the prophet and priest Hananiah. Jeremiah listens to Hananiah predict that their captivity will last only two years more and agrees that he too wishes that it were so. However, Jeremiah later comes back to Hananiah and confronts him with the conviction that he did not receive that message from God and because he has proclaimed in the name of the Lord a message the Lord did not give him, the Lord would deal harshly with him. The moral of the story could be understated as: be careful of those who promise easy answers. More to the point, the moral is the way forward is not in assessing public opinion and responding to market demands.

A third message I receive from my reading thus far is the we have hope but that hope functions on God's time-table not ours. I'll admit that my reading of Jeremiah was getting tedious. It felt hopeless and heavy. Around chapters 29 and 30, Jeremiah's tone begins to make a turn toward the hopeful. The principle difference between Jeremiah's message of hope and the easy answers of the prophets Jeremiah condemns seems to concern timetable. The "false prophets" proclaim that deliverance is coming soon. Jeremiah's message is that deliverance is coming after seventy years (Jeremiah 29:10). Our situation is long-term but temporary. In Jeremiah 29, Jeremiah gives an interim ethic that belongs to people in a time of exile.

Finally, Jeremiah's message is theocentric. Jeremiah 30:22 contains this promise, "So you will be my people and I will be your God." The problem I see with so much of the current discussion about the decline of the church is that prescriptions different commentators tend to give still function on an existing continuum. Either we should return to a form of Christianity that existed in the past (that we imagine existed in the past) OR that the way forward is to continue forward with a progressive agenda. All of this seems to me to be pots trying to tell the Potter how to mold the clay. On the other side of whatever contemporary trend we are in, God will have faithful people who have yielded themselves to God's re-forming and they will have a remarkable experience of new life. As a post-script, I would say that we as Christian should remember that God's work does not culminate with reorganization, reformation, or revolution. God's work culminates in resurrection--new life emerging out of the tombs of real and painful death.

Richard Douthat in his much discussed article for the New York Times entitled, "Can Liberal Christianity Be Saved?" identified the Episcopal Church's liberalism as the reason for its decline. Douthat argument rests on two assumptions. Assumption 1--the Liberal trends were made to appeal to people. He wrote "Yet instead of attracting a younger, more open-minded demographic with these changes, the Episcopal Church’s dying has proceeded apace." Assumption 2--the conservative retrieval or return to traditional Christian configurations is the answer.

Both writers maintain description of the church and it's position in the world in terms of a left/right, progressive/conservative, liberal/orthodox dichotomy. Forecasters often identify the demise of the church and it's potential for recover, reformation or revolution in the church's capacity to respond to new needs and expectations of people. Yet, I wonder how the issues might look if we spoke of our situation in terms of a portion of biblical narrative rather than the categories available to us through culture.

I have recently been working my way through Jeremiah and I am frequently reminded of these discussions and others as I listen to Jeremiah's words to an exiled Judah. No, our exile did not come out of a violent experience of culture. No, we have not been physically displaced. We cannot compare the severity of our growing displacement with the oppression experienced by the 6th Century BC Jews. At the same time, because we lack these salient confrontations with reality, we also may not see clearly what is taking place. We are like the exiles in that increasingly we find ourselves at the margins of the culture.

Increasingly Christian faith enters the American public as a stranger in a strange land What lessons might we learn about living faithfully in exile? First, we can accept the changing situation as a context for readdressing the level of your faithfulness. In the early portions of Jeremiah, the Babylonian captivity is understood as God's act to bring about the repentance of the people. Even going as far as declaring the Nebuchadnezzar is God's servant (Jeremiah 27:6). Today, we might not believe that God orders national affairs in order to discipline and chastise God's people (maybe some people do, I don't). Regardless, learning to see our situation through this biblical narrative means asking questions about the nature of our faithfulness in the midst of this changing situation.

A second recurring theme in Jeremiah that I find both instructive and challenging is Jeremiah's confrontation of prophets who give answers that sound good but are in fact not from God. One particularly poignant example occurs in Jeremiah 28 where the prophet Jeremiah confronts the prophet and priest Hananiah. Jeremiah listens to Hananiah predict that their captivity will last only two years more and agrees that he too wishes that it were so. However, Jeremiah later comes back to Hananiah and confronts him with the conviction that he did not receive that message from God and because he has proclaimed in the name of the Lord a message the Lord did not give him, the Lord would deal harshly with him. The moral of the story could be understated as: be careful of those who promise easy answers. More to the point, the moral is the way forward is not in assessing public opinion and responding to market demands.

A third message I receive from my reading thus far is the we have hope but that hope functions on God's time-table not ours. I'll admit that my reading of Jeremiah was getting tedious. It felt hopeless and heavy. Around chapters 29 and 30, Jeremiah's tone begins to make a turn toward the hopeful. The principle difference between Jeremiah's message of hope and the easy answers of the prophets Jeremiah condemns seems to concern timetable. The "false prophets" proclaim that deliverance is coming soon. Jeremiah's message is that deliverance is coming after seventy years (Jeremiah 29:10). Our situation is long-term but temporary. In Jeremiah 29, Jeremiah gives an interim ethic that belongs to people in a time of exile.

Finally, Jeremiah's message is theocentric. Jeremiah 30:22 contains this promise, "So you will be my people and I will be your God." The problem I see with so much of the current discussion about the decline of the church is that prescriptions different commentators tend to give still function on an existing continuum. Either we should return to a form of Christianity that existed in the past (that we imagine existed in the past) OR that the way forward is to continue forward with a progressive agenda. All of this seems to me to be pots trying to tell the Potter how to mold the clay. On the other side of whatever contemporary trend we are in, God will have faithful people who have yielded themselves to God's re-forming and they will have a remarkable experience of new life. As a post-script, I would say that we as Christian should remember that God's work does not culminate with reorganization, reformation, or revolution. God's work culminates in resurrection--new life emerging out of the tombs of real and painful death.

Monday, July 16, 2012

Responding to Denominational Decline

Today,

Diana

Butler Bass responded to a New York Times column

by Ross Douthat. They were both offering interpretation of the numeric

decline in denominations in relation to political leanings and/or movements in

“liberal” denominations. I would

offer two additional pieces of statistical information for the discussion. First, Bass is not a sociologist

trained in statistical analysis.

Second, Douthat is not a sociologist trained in statistical analysis. I suspect that a sociologist grounded

in statistical analysis would say that there are too many confounding variables

to deduce a correlation between one aspect of a denomination’s character (like it's perceived political leanings) and its rise or fall in attendance or membership.

I do wonder to what extent the denominational numbers matter. To me it’s a bit like the reporting of

box office receipts for a movie or the number of viewers of a TV show. Those numbers do not tell me whether I

will enjoy the film or not.

Numerical decline of denominations tells us very little—if

anything—about what it means to be a faithful follower of Jesus Christ. Personally, I have found that the

harder I try to fulfill the expectations of a category—Progressive, Liberal,

Evangelical, Emergent, Missional—the less faithful I actually am. And when I think I've got some responsibility for the "scores" of the groups to which I've been trying to uphold, my faithfulness goes down even more. I’ll admit that I did try for many

years to make sure I really was an Evangelical. It’s not without some grief that I say, “I’ve given that

up. I’m ready to just be

Christian.”

Bryan

Feille once asked the question, “What’s the difference between tradition and

traditionalism?” By “tradition” he

meant the theological sense of one’s cultural-historical faith stream (i.e.,

Stone-Campbell, Reformed, Western).

Tradition is a theological resource if it is part of the dialogue. It becomes traditionalism when we feel

that we must adhere to our cultural-religious stream no matter what. For example, when the Stone-Campbell way of doing

things overrides any other considerations. When we choose to be ecumenical simply because we think

that’s what in our DNA to do. So

too with contemporary categorizations: if they help our conversation,

great. If we perceive that the

loss of membership in some cultural grouping is an actual loss of something

precious, then we risk relinquishing our own discernment processes. We hand them over to the trends

advocated in our grouping.

Faithfulness involves discernment.

The groups to which we think we belong can be helpful as theological

resources but become the sole mechanisms of decision. The political or apolitical nature of a person and/or

congregation’s discipleship must emerge out of their discernment—out of their

attempts to be faithful in a complex world. That shouldn’t be conditioned by what it might do to the

scoreboard for our group or denomination.

I would argue that the conversation between Douthat and Bass is the wrong

conversation to begin with. For the average reader of news media about religion, the issue of denominational decline is news only in the sense that movie receipts and TV ratings are news--quantitative trivia not qualitative value. The question for them needs to be how to respond faithfully in a world where cultural assumptions toward religion in general has changed--how to provide a faithful witness in a pluralistic context.

That’s

not to say that numbers don’t matter.

As a local church pastor, I can’t worry a about declines in the

Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) as a whole. I can—indeed must--accept

responsibility for the decline in average worship attendance at First Christian

Church, Arlington, Texas—which has been painfully significant during my

tenure. In terms of faithfulness,

here’s where I think we stand: I serve a congregation of people willing to love

and support one another. It is a

congregation deserving of growth because it is a congregation that does good

for the people who are here. It is

a body of faithful Christians who can be entrusted with the care of new

Christians. The biggest reason we have declined is that I haven’t paid enough

attention to growth. I don’t think

that’s because of my politics, theology, or denominational leaning. There are several reason for this

decline but the one I bear the greatest responsibility for are the following:

(1) we have not created an invitational culture—one where people invite other

people to worship with them; (2) we have a small and ineffective response to

visitors after people visit; (3) our services—both traditional and

contemporary—rely too heavily on insider language. Denominational declines are

ultimately the aggregates of thousands of local churches that are in

decline. Each of those local

churches have unique reasons for their decline and must make their own

decisions about how to respond. These are the confounding variables that the

analysis of Bass and Douthat do not account for, in fact cannot account for, in

their analysis.

Friday, July 13, 2012

Transitions

Earlier this summer, I made the decision to present as many of my presentations--mainly preaching--in an extemporaneous manner and to chronicle my experiences.

One of the difficulties with extemporaneous preaching is transitions. This has been the case even when using a normal organizational pattern in public speaking. In basic public speaking transitions have a formulaic quality. There's an introduction, body and conclusion. In the body of the speech, main points are covered. Usually there are 2, 3 or 4 main points. The transitions occur between the main points. Typically, the speaker should summarize the main point, draw it to a close and then move to the next main point. I teach my students to be very obvious about this. They are to signpost. Signposting is using a word like "First, Second, Third." After they signpost, they state their main point as a propositional statement.

Preaching, at least as I am trying to do it, is not nearly as direct. Stating the main conclusion and the propositional supporting points at the beginning of each main point doesn't always happen. It is frequently better to withhold the conclusion until much later. Aesthetically delaying the conclusion of a main point bBuilds suspense

More accurately delaying making the "points" in a sermon reflects the way one comes to theological insight from a text. This is the idea of inductive preaching as taught by Fred Craddock in As One Without Authority. Craddock explains in preaching, the pastor is a servant both of the Word and of the People. The preacher invites the two to come together rather the dictatorially spelling out the "truths" to which he or she expects consent from the congregation. A sermon that orally reproduces the process of thinking sends the message that faith is a process--we don't come at the text with all the answers already in place; the ideas form through reflection, wrestling, study, etc. This means that sermons, as least as I typically conceive them, do not have easily discernible "points" in the same way that a speech might. Instead, they have what David Buttrick calls "moves."

Under normal circumstances, remembering to do all that you need to do to make a transition work is difficult. On sample outlines, I used actually write in the transition lines. When you're trying to build observations and reflections to reach a conclusion that will serve as a transitions, it is difficult to be patient with your own recollection and delay reaching the conclusion. In short, to sustain effective extemporaneous speaking, I would have to learn ways to effectively transition from one point to the next.

Friday, June 29, 2012

Two Reactions to the Supreme Court Decision Yesterday

Kathryn M. Lohre, NCC President, "Christians believe that human beings—all of them—are infinitely-valued children of God, created in God’s image. Adequate health care, therefore, is a matter of preserving what our gracious God has made. That is why churches (and other religious communities) have established so many hospitals and other places of healing. And why we are convinced that health care is not a privilege, reserved for those who can afford it, but a right that should be available, at high quality, to all." "NCC welcomes U.S. Supreme Court decision upholding individual health insurance requirement" from www.nccusa.org

Thursday, June 28, 2012

Dying Denominations

Awhile back, Derek Penwell wrote a blog post inviting Christians to reassess the priority we place on the death of denominations. In this article, he wrote, “Today, denominational loyalty seems a quaint bit of nostalgia, like the gilded memories of neighborhood soda fountains and day baseball.” Can we roll our eyes now? The social impact of denominational loyalty is more substantial than soda fountains and baseball given by themselves the number of universities and hospitals started by denominations. The past accomplishments and social goods gained by denominations do not by themselves justify denominational continuation. Plenty of long-standing, historic institutions are proving that they must either radically revision their function (as in the case of public libraries) or face the inevitability of their obsolescence (as in the case of the US Postal Service). If denominations no longer serve a useful purpose, they no longer serve useful purpose. We can have a dignified burial. But the obituary should have a broader view of their accomplishments than the one Penwell envisions—that they once provided a shopping guide for people looking for a congregation where their needs were met.

Denominations have provided the institutional structure for education, hospitals, nursing homes, children’s homes, emergency relief, global missions, new church development, ministerial education and accountability, discipleship ministries for young people in the forms of camps and conferences, bible curriculum, political advocacy (occasionally), ecumenical cooperation and the list goes on. We do indeed need to accept that each of the things I just mentioned is being done differently today. Few of the large institutions like universities, hospitals and nursing homes can rely on denominational funding solely and consequently balance denominational governance with other stakeholders. Churches of Christ have shown that global ministries can be sustained without a denominational structure. Ecumenical institutions are facing the very same shifting cultural realities that denominations face. Ministry education and accountability and church camps, if they are as necessary as I think they are, can be built beyond the formal denominations that have been their loci thus far. I not going to be that person who just thinks denominations have to stay alive because “we’ve always done it that way.” However, we do need to take stock of what the “it” we’ve done through denominations really is.

The decisions we have to make are indeed bigger than whether our denomination needs rebranding. These decisions include a lot of things that are important but not readily visible to the typical church-goer. In a most cases, I don’t think we should spend too much time trying to explain it to everyone. When I go to the doctor, I don’t ask for a lecture on the state of the professional organizations to which he or she belongs. I want the doctor to be board certified. I do not want a comprehensive knowledge of what board certification really entails. It matters to my doctor and therefore indirectly to me.

When parents pass away, the children or grandchildren have the painful task of going through the house and deciding what needs to be kept and moved and what needs to be thrown out. If denominations are dying, we the children of denominations have that very same task. If we dismiss our support for denominations too quickly we may discover that we did not make plans for how to accomplish some essential functions at a time when it’s too late to do anything about it--that we threw out something we really did need just because we didn’t think we needed it at that exact moment. I’m of the opinion that we can be both realistic and faithful as we do so, but I don’t think it’s faithful to point at the denominational house of our parents and say, “all that’s in there are a few quaint memories.”

Denominations have provided the institutional structure for education, hospitals, nursing homes, children’s homes, emergency relief, global missions, new church development, ministerial education and accountability, discipleship ministries for young people in the forms of camps and conferences, bible curriculum, political advocacy (occasionally), ecumenical cooperation and the list goes on. We do indeed need to accept that each of the things I just mentioned is being done differently today. Few of the large institutions like universities, hospitals and nursing homes can rely on denominational funding solely and consequently balance denominational governance with other stakeholders. Churches of Christ have shown that global ministries can be sustained without a denominational structure. Ecumenical institutions are facing the very same shifting cultural realities that denominations face. Ministry education and accountability and church camps, if they are as necessary as I think they are, can be built beyond the formal denominations that have been their loci thus far. I not going to be that person who just thinks denominations have to stay alive because “we’ve always done it that way.” However, we do need to take stock of what the “it” we’ve done through denominations really is.

The decisions we have to make are indeed bigger than whether our denomination needs rebranding. These decisions include a lot of things that are important but not readily visible to the typical church-goer. In a most cases, I don’t think we should spend too much time trying to explain it to everyone. When I go to the doctor, I don’t ask for a lecture on the state of the professional organizations to which he or she belongs. I want the doctor to be board certified. I do not want a comprehensive knowledge of what board certification really entails. It matters to my doctor and therefore indirectly to me.

When parents pass away, the children or grandchildren have the painful task of going through the house and deciding what needs to be kept and moved and what needs to be thrown out. If denominations are dying, we the children of denominations have that very same task. If we dismiss our support for denominations too quickly we may discover that we did not make plans for how to accomplish some essential functions at a time when it’s too late to do anything about it--that we threw out something we really did need just because we didn’t think we needed it at that exact moment. I’m of the opinion that we can be both realistic and faithful as we do so, but I don’t think it’s faithful to point at the denominational house of our parents and say, “all that’s in there are a few quaint memories.”

Sunday, June 24, 2012

Speaking Notes

Here are the speaking notes that I used to present Sunday's sermon. There was a full manuscript that I worked through a couple of times on Sunday morning. This is what it would I had on a piece as notes:

Familiarity breeds neglect—love, compassion, peace,

service. Grace—pictures of

grace—frilly lace, a red stamp “paid in full.”

Romans would cause us to rethink it.

Bible teaching:

(Grace begins and ends with God)

p. 916, “God’s righteousness.”

Understanding 3:23.

God created us for relationship; we only have relationship

by God’s initiative.

Paul challenged the belief that people could achieve God’s

righteousness on their own.

Nature

of Law.

The

Effect of Law

The

goodness of law

The agency of Jesus Christ

note

a—the faithfulness of Jesus Christ.

Atonement

Differences in our typical understanding

Grace

begins with human need.

Not

a bad place to start. . . but . . . Grow up!

If we’re going to understand the magnitude of the word

grace, we have to stem the impulse to make grace about us. Grace is a word that stands for God’s

righteousness—that is, the very character of God—embodied in Jesus Christ—the

voice, presence, and power of God to reconcile people to God’s self.

3 tendencies. Step

on toes/form a support group

-Needy

--Resume Christians

--Tragic Shrug/Cheap Grace

How respond?

The rest of Romans answers.

Saturday, June 23, 2012

Backsliding

It's Saturday night. I have now completed work on the sermon for Sunday--a full 27 hours later than I'm comfortable with. I had struggled with the text for 12 days. Worked on creating an actual outline for three days. I finally had to give in and write a manuscript. The problem is the difficulty of the concepts.

Romans 3:21-31 is a dense passage in Romans with a number of themes from the whole book coming together and overlapping. Since my church generally frowns on sermons lasting three hours (17 minutes is par), I opted not to try to be comprehensive with the text. So I chose to take one focus on the text.

What strikes me about it is that "Grace" is generally something we view as very personal and very individual. "I once was lost" Grace saved "a wretch like me." Paul's point seems emphatic that grace emerges from the nature and character of God. It emerges out of God's righteousness. This is contrary to some of my embedded theology that always regarded grace as somehow a suspension of God's righteousness. Grace begins and ends with God and if grace doesn't overwhelm us then we probably haven't understood it.

I gave in because I couldn't convince myself that I was going to be able to say all that clearly without having written the words out at least once. I'm not claiming that the manuscript I have written is coherent. I'm just saying, I feared that working from an outline given the complexity of the thoughts I want to convey would have been disastrous.

This tends to be my problem with the prevailing dogma in speech instruction about extemporaneous speaking it over looks the necessity in so many instances to write your thoughts down word for word. (1) Sometimes people need to write a manuscript in order to get thoughts clear in their own minds--that was the case this week; (2) Sometimes people need to write a manuscript or else risk venturing down too many concepts (chasing rabbits)--a danger with this text; (3) Sometimes people need to write manuscripts so they can carefully choose wording that can will be clear to their audience.

Romans 3:21-31 is a dense passage in Romans with a number of themes from the whole book coming together and overlapping. Since my church generally frowns on sermons lasting three hours (17 minutes is par), I opted not to try to be comprehensive with the text. So I chose to take one focus on the text.

What strikes me about it is that "Grace" is generally something we view as very personal and very individual. "I once was lost" Grace saved "a wretch like me." Paul's point seems emphatic that grace emerges from the nature and character of God. It emerges out of God's righteousness. This is contrary to some of my embedded theology that always regarded grace as somehow a suspension of God's righteousness. Grace begins and ends with God and if grace doesn't overwhelm us then we probably haven't understood it.

I gave in because I couldn't convince myself that I was going to be able to say all that clearly without having written the words out at least once. I'm not claiming that the manuscript I have written is coherent. I'm just saying, I feared that working from an outline given the complexity of the thoughts I want to convey would have been disastrous.

This tends to be my problem with the prevailing dogma in speech instruction about extemporaneous speaking it over looks the necessity in so many instances to write your thoughts down word for word. (1) Sometimes people need to write a manuscript in order to get thoughts clear in their own minds--that was the case this week; (2) Sometimes people need to write a manuscript or else risk venturing down too many concepts (chasing rabbits)--a danger with this text; (3) Sometimes people need to write manuscripts so they can carefully choose wording that can will be clear to their audience.

Friday, June 22, 2012

Quotations

I like quotations, pithy words someone else has written that say things better than I can say them myself. I recently encountered this quotation from C. S. Lewis, “Friendship is born at that moment when one person says to another: 'What! You too? I thought I was the only one.'" I also like finding quotations in context, being able to read what's around them. Google Books is a great aid in that effort.

What I found when I went looking for this quotations is this from The Four Loves, "The typical expression of opening Friendship would be something like, 'What? You too? I thought I was the only one.'" Then a little bit later in that paragraph, "It is when two such persons discover one another, when, whether with immense difficulties and semi-articulate fumblings or with what would seem to us amazing an elliptical speech, they share their vision. It is then that friendship is born. And instantly they stand together in an immense solitude."

It's entirely possible that somewhere else C. S. Lewis said, “Friendship is born at that moment when one person says to another: "What! You too? I thought I was the only one" but, I didn't find it. I did find dozens of books quoting it this way without any citation. This example is fairly harmless as the reworked quotation--if it is indeed reworked--says more or less what Lewis was saying. Lewis wasn't as absolute in the context I found but, people generally understand hyperbole as hyperbole. It's is a good example of how some ways of expressing things begin to take a life of their own. It is is easy to become reckless with quotations in writing and speaking--especially when the quotation is that good.

What I found when I went looking for this quotations is this from The Four Loves, "The typical expression of opening Friendship would be something like, 'What? You too? I thought I was the only one.'" Then a little bit later in that paragraph, "It is when two such persons discover one another, when, whether with immense difficulties and semi-articulate fumblings or with what would seem to us amazing an elliptical speech, they share their vision. It is then that friendship is born. And instantly they stand together in an immense solitude."

It's entirely possible that somewhere else C. S. Lewis said, “Friendship is born at that moment when one person says to another: "What! You too? I thought I was the only one" but, I didn't find it. I did find dozens of books quoting it this way without any citation. This example is fairly harmless as the reworked quotation--if it is indeed reworked--says more or less what Lewis was saying. Lewis wasn't as absolute in the context I found but, people generally understand hyperbole as hyperbole. It's is a good example of how some ways of expressing things begin to take a life of their own. It is is easy to become reckless with quotations in writing and speaking--especially when the quotation is that good.

Thursday, June 14, 2012

Assessment

My third purely extemporaneous sermon in a row can be found here. It was the first sermon in a

series on Romans. The experience around

this sermon shows both the benefits and the pitfalls of extemporaneous

sermons.

Benefits

1. Decreased preparation anxiety. When I was preparing the sermon in manuscript

form, Fridays—sermon writing days—were filled with tossing, turning, and

sweating. The outline is a lot less

stressful to create.

2. Ability to think about the flow. When you outline a presentation, you’re able

to see clearly how the pieces fit. That’s

not always easy with a manuscript.

Pitfalls

1. Sloppiness. One of

the biggest reasons given for preaching from a manuscript is precision. And this particular sermon lacked a lot of

it. The edict of Claudius expelling the

Jews from Rome came in 49 CE not 54 CE.

I used four examples—Augustine, Luther, Wesley, and Barth. Three out of four were European, not four out

of five (I said "four out of five").

2. Another problem that I experienced with this sermon that I

frequently experience is running out of air toward the end of sentences. When I prepare the sermon for podcasting, I

use Audacity. I can see the wavelengths

and notice as the sermon progresses that voice strength gets measurably

lower. Part of that could be

fatigue. This would have been the third

time that day I preached the sermon.

Part of it also comes from declining confidence. My mouth is speaking, my brain is trying to

process the next thought, and somewhere in between the two, my volume goes

down. I don't know that this is better or worse with extemporaneous sermons. It doesn't happen with a manuscript but there are many other deliver problems that tend to come with manuscripts (like of eye contact or the frequent head bob, monotone). The comparison would really need to be between preaching from a memorized manuscript versus extemporaneously.

Saturday, June 09, 2012

OneNote on computer and on iPhone

Here are screenshots of Sunday's outline expanded and collapsed. OneNote also has an iPhone app. I can edit the note but it will not show the numbers on the outline.

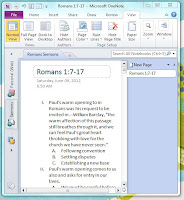

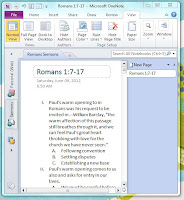

To the left: Here' how OneNote Looks collapsed. You see that right above the "Romans 1:7-17" label is a tab that says "Roman Sermons." On the right hand side you see a column that has the name of the page. Pages can be added to each tab and reordered. The parts of the outline can be expanded and collapsed with a button click. Formatting the outline--i.e., creating Harvard-style--is relatively simple but not automatic as far as I can tell.

To the left: Here' how OneNote Looks collapsed. You see that right above the "Romans 1:7-17" label is a tab that says "Roman Sermons." On the right hand side you see a column that has the name of the page. Pages can be added to each tab and reordered. The parts of the outline can be expanded and collapsed with a button click. Formatting the outline--i.e., creating Harvard-style--is relatively simple but not automatic as far as I can tell.

To the Right: Here is how OneNote looks expanded. The outline looks and functions

the way I'm wanting my outline to work.

the way I'm wanting my outline to work.

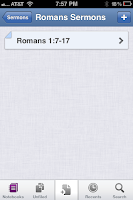

Here are how the same outline looks in the OneNote iPhone app.

The home screen shows the notebooks that you have in a SkyDrive (cloud files through Hotmail and maybe some other programs). Once selected, the notebook shows a list of the pages. Unlike in the computer version the pages cannot be reordered here. So far as I can tell, you can't put new notes into a notebook on the iPhone either. You can simply create unfiled notes--I think.

The home screen shows the notebooks that you have in a SkyDrive (cloud files through Hotmail and maybe some other programs). Once selected, the notebook shows a list of the pages. Unlike in the computer version the pages cannot be reordered here. So far as I can tell, you can't put new notes into a notebook on the iPhone either. You can simply create unfiled notes--I think.

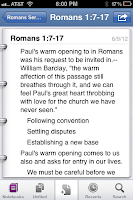

Finally, the outline above looks like this on the iPhone. Levels are indented. No movement, collapsing or expanding. But you can add text to an existing note. There is an upgrade option, I'll see later if that's worth it.

Finally, the outline above looks like this on the iPhone. Levels are indented. No movement, collapsing or expanding. But you can add text to an existing note. There is an upgrade option, I'll see later if that's worth it.

To the left: Here' how OneNote Looks collapsed. You see that right above the "Romans 1:7-17" label is a tab that says "Roman Sermons." On the right hand side you see a column that has the name of the page. Pages can be added to each tab and reordered. The parts of the outline can be expanded and collapsed with a button click. Formatting the outline--i.e., creating Harvard-style--is relatively simple but not automatic as far as I can tell.

To the left: Here' how OneNote Looks collapsed. You see that right above the "Romans 1:7-17" label is a tab that says "Roman Sermons." On the right hand side you see a column that has the name of the page. Pages can be added to each tab and reordered. The parts of the outline can be expanded and collapsed with a button click. Formatting the outline--i.e., creating Harvard-style--is relatively simple but not automatic as far as I can tell.To the Right: Here is how OneNote looks expanded. The outline looks and functions

the way I'm wanting my outline to work.

the way I'm wanting my outline to work. Here are how the same outline looks in the OneNote iPhone app.

The home screen shows the notebooks that you have in a SkyDrive (cloud files through Hotmail and maybe some other programs). Once selected, the notebook shows a list of the pages. Unlike in the computer version the pages cannot be reordered here. So far as I can tell, you can't put new notes into a notebook on the iPhone either. You can simply create unfiled notes--I think.

The home screen shows the notebooks that you have in a SkyDrive (cloud files through Hotmail and maybe some other programs). Once selected, the notebook shows a list of the pages. Unlike in the computer version the pages cannot be reordered here. So far as I can tell, you can't put new notes into a notebook on the iPhone either. You can simply create unfiled notes--I think. Finally, the outline above looks like this on the iPhone. Levels are indented. No movement, collapsing or expanding. But you can add text to an existing note. There is an upgrade option, I'll see later if that's worth it.

Finally, the outline above looks like this on the iPhone. Levels are indented. No movement, collapsing or expanding. But you can add text to an existing note. There is an upgrade option, I'll see later if that's worth it. Saturday, June 02, 2012

MicroSoft OneNote

After a few years of ignoring OneNote, I was playing with it this afternoon--I recently acquired a full version of Microsoft Office with OneNote. It does pretty much everything I need an outliner to do. I don't know if it will import/export to OPML yet. At the church office, we have Apples and I'm still trying to decide between OmniOutliner and Tree. The difference is about $25. OmniOutliner is about $40 and Tree is about $15.

Tuesday, May 29, 2012

Memorized Manuscript vs. Extemporaneous Preaching

Sermons from the last few weeks at First Christian Church can be found here. The sermon "I Will Survive" was preached on May 13. It was my traditional pattern of crafting a manuscript and then reducing key words and portions of the manuscript to a piece of paper--normal paper printed landscape with two columns, folded in half. I practice this so that more or less I am preaching from memory. There were a couple of long quotations that were read. The sermon "Wouldn't It Be Nice" was preached on May 20. It was preached from an outline only. There was no manuscript anywhere. Both sermons were good sermons for me.

The extemporaneous sermon had problems with fluency at the beginning. Too many vocalized pauses. The memorized sermon had problems toward the end. When I got to the section where I used the "Praise the Lord" refrain, the refrain "Praise the Lord" comes out flat because I was trying to remember the next pair of experiences.

This past week, May 27, I again preached from an outline. The sermon was worse than the previous two but, I don't know that the outline was to blame.

1. I had convoluted cultural lead-ins--The sermon series has taken "B-Side Hits" (i.e., pop music songs that were originally released on the B-sides of a single that did better than the A side) and compared them to texts from the Minor Prophets (i.e., the B-Side of biblical prophetic literature. However, I also used Peter Bregman's "Two Lists You Should Look At Every Morning." Trying to incorporate references both to "Focus" and "Ignore" lists and "Everyday" by Buddy Holly got convoluted.

2. I had too many ideas. Fred Craddock warns than when preachers preach three point sermons they often end up with three sermonettes rather than one complete sermon. That was the case here.

3. I didn't have strong examples or narratives. The supporting material was lacking.

4. Failure to rehearse. One of the things I'm finding thus far with the extemporaneous approach is that I struggle to find the motivation to practice the way I do when I'm speaking from a manuscript.

The extemporaneous sermon had problems with fluency at the beginning. Too many vocalized pauses. The memorized sermon had problems toward the end. When I got to the section where I used the "Praise the Lord" refrain, the refrain "Praise the Lord" comes out flat because I was trying to remember the next pair of experiences.

This past week, May 27, I again preached from an outline. The sermon was worse than the previous two but, I don't know that the outline was to blame.

1. I had convoluted cultural lead-ins--The sermon series has taken "B-Side Hits" (i.e., pop music songs that were originally released on the B-sides of a single that did better than the A side) and compared them to texts from the Minor Prophets (i.e., the B-Side of biblical prophetic literature. However, I also used Peter Bregman's "Two Lists You Should Look At Every Morning." Trying to incorporate references both to "Focus" and "Ignore" lists and "Everyday" by Buddy Holly got convoluted.

2. I had too many ideas. Fred Craddock warns than when preachers preach three point sermons they often end up with three sermonettes rather than one complete sermon. That was the case here.

3. I didn't have strong examples or narratives. The supporting material was lacking.

4. Failure to rehearse. One of the things I'm finding thus far with the extemporaneous approach is that I struggle to find the motivation to practice the way I do when I'm speaking from a manuscript.

Friday, May 25, 2012

Extemporaneous Funerals

Since making the commitment to work extemporaneously, I have had four funerals. They were all within one week. Two on Saturday--graveside for one, community building for the other. One on Monday in a Fort Worth Funeral Home and another on Tuesday. This is unusually high volume but, they were all well-lived lives. Two of the people were over ninety, one in her eighties, and one in his seventies. All had been cared for lovingly by their family. None died suddenly. While every death brings grief, some are less difficult for the pastor. These were not difficult. It was easy to affirm the family that they had cared for their loved one and easy to affirm that the people involved had indeed fought the good fight, finished the race, and received the reward God had planned for them.

Typically, I write out every word of a funeral service--call to worship, invocation, life-marks, pastoral prayer, the message of hope, and benediction. Plus comital and prayers for the graveside service. In the services, I worked from an outline. I jotted down structure and keywords for the prayers, family member names and dates and events on the life marks and an outline for the messages of hope.

In these situations, the extemporaneous approach didn't work well. Word-choice was at issue. Frequently it felt like I was rushing things. Where I got to the part of identifying our spiritual resources the content seemed thin. I don't work from a canned message of hope. There are some things that I say frequently at funerals but, I also try to find a unique way to say them. So, I would say that I'm not satisfied with the content of the messages. I'm not particularly satisfied with the eye-contact. On the plus side, it was an intensely high number of speaking occasions to get done in a short amount of time. The extemporaneous approach did help with the demands of the week.

Typically, I write out every word of a funeral service--call to worship, invocation, life-marks, pastoral prayer, the message of hope, and benediction. Plus comital and prayers for the graveside service. In the services, I worked from an outline. I jotted down structure and keywords for the prayers, family member names and dates and events on the life marks and an outline for the messages of hope.

In these situations, the extemporaneous approach didn't work well. Word-choice was at issue. Frequently it felt like I was rushing things. Where I got to the part of identifying our spiritual resources the content seemed thin. I don't work from a canned message of hope. There are some things that I say frequently at funerals but, I also try to find a unique way to say them. So, I would say that I'm not satisfied with the content of the messages. I'm not particularly satisfied with the eye-contact. On the plus side, it was an intensely high number of speaking occasions to get done in a short amount of time. The extemporaneous approach did help with the demands of the week.

Outliner--The Ball That Get's Moved

Each Fall as football season approaches, Charlie Brown is tricked into attempting to kick a football as Lucy holds it. Each year he tries even though he knows that she will pull it away at the last second, he will kick into thin air and the inertia of his foot meeting no resistance from a football will carry him sailing into the sky and land him flat on his back.

Finding a computer outliner is that experience for me. I have tried repeatedly for well over a decade. There are PLENTY of computer outliners available in freeware, shareware, and commercial form. Some are fully featured and others are sparse. There are one-pane, two-pane and three-pane versions. I have tried many. The problem that I have found is that the ones that do what I need them to do are not stable and the ones that are stable don't do what I need them to do. Or they are prohibitively expensive.

NEEDS:

Finding a computer outliner is that experience for me. I have tried repeatedly for well over a decade. There are PLENTY of computer outliners available in freeware, shareware, and commercial form. Some are fully featured and others are sparse. There are one-pane, two-pane and three-pane versions. I have tried many. The problem that I have found is that the ones that do what I need them to do are not stable and the ones that are stable don't do what I need them to do. Or they are prohibitively expensive.

NEEDS:

- Single-pane--when composing a speech outline, it is hard for me to look back and forth between claim (i.e., the topic line of an outline) and data & warrant material (i.e., the substructure of a main point). I've tried. It doesn't work for me.

- Numbered lists--Because I've been doing this for a number of years, I know where I am on a speech using the old fashioned, Harvard style (I, II, A, B, 1, 2,) style of outlining. I prefer something that does exactly that. I need something that at least numbers. It's hard to "signpost" orally if your outline doesn't designate A, B, C and 1, 2,3.

- The ability to easily move chunks of the outline around. One of the chief benefits of an outline for speech purposes is to see quickly the flow and development of an argument. Just having something that looks like an outline (which I can produce in MS Word) will not achieve what I need it to achieve. In Outline View, Word has some navigational tools but it doesn't easily move chunks (i.e., a main point AND it's substructure).

WANTS:

- Cross platform--I use an iPhone, Mac (at the office) and PC (at home).

- Affordable.

- The ability to expand and collapse units.

ATTEMPTS:

- Omni-Outliner--works great in Mac. Doesn't work in any other environment.

- Tree--seems to work so far well in Mac. Doesn't work in any other environment.

- ThinkLinkr--seemed perfect at first. Works online (like google docs) but has proven to be unacceptably unstable on many computers.

- NoteMap--a PC outliner designed for lawyers, effective. Prohibitively expensive (over $200).

PLAN:

I will be using Carbon Fin's Outliner Online for any idea-jotting to do on the iPhone or other computer. I can import it as OPML into either OmniOutliner or Tree on the Mac. Still looking for acceptable version to use on the PC.

Labels:

Carbon Fin Outliner Online,

NoteMap,

OneNote,

outliner,

ThinkLinkr,

Tree

Going Extemporaneous

A couple of weeks ago, I was at a departmental meeting for adjunct and full-time speech faculty for Brookhaven. The issue of extemporaneous versus manuscript speeches came up. The crux of the discussion: manuscript speeches are bad--very, very bad. Most of the other faculty give very low grades to students who read excessively during their speech. There was a clear desire for the rest of us to grade "read" speeches in a similar way.

The rationale is sound. Taking the time to write a manuscript is inefficient. It decreases eye-contact. It sounds written rather than sounding like speech, etc. We are the only department that teaches oral communication and therefore we need to insure that students are developing oral skills not merely vocalizing their writing skills. I was the one objector in the room.

My objection emerges from my experience. The extemporaneous (i.e., speaking from an outline rather than a manuscript) dogma is what I lived with as an undergraduate. At no point in either my undergraduate or graduate education was I ever taught how to write for oral communication. But, there is a need to learn to write for orality. The one I remember thinking about as an undergraduate was that of professional speech writing. But there are others situations where it is needed. Despite the potential for us to need to know how to write for oral communication, we were never taught it.

In Seminary at Brite Divinity School, the overwhelming bias--at least while I was there--was in favor of manuscript sermons. The reasons we gave for using a manuscript also make sense. When dealing with theological concepts we do not want to be sloppy with word choice. Also, a manuscript provides for better time management. I know to the minute how long a 3 page sermon will last but a half-page outline could be done in five minutes or take as long as an hour.

I adopted the manuscript practice. On many Sundays I read my sermon word-for-word from the pulpit. Starting around 2000, I started to memorize (more or less) my sermon manuscript and deliver the sermon with minimal notes. If I can run through the sermon three times before the first worship service, I can pretty accurately recreate the manuscript from memory. This stopped as my constant approach in about 2005 when my third child was born. The lack of sleep made it a lot more difficult. I've recently returned to my commitment to preach without a manuscript in front of me each Sunday. But whether preaching from a manuscript with me in the pulpit or preaching from memory and minimal notes, there has usually been a manuscript somewhere that I had prepared before preaching.

So, I had a dilemma. My speech com undergraduate education and teaching needs pushed for extemporaneous approach. My homiletics training preferred a manuscript. My speech teaching responsibilities asked me to give a lower grade to a practice that I myself habitually and intentionally engaged.

In part to relearn how to do extemporaneous speaking and in part to test out the competing claims about mode of delivery, I have made a personal decision to give--as best I can--every speech (sermon, report, homily) in an extemporaneous mode between now and the start of school. I will chronicle my experiences and draw conclusions based on what I learn.

The rationale is sound. Taking the time to write a manuscript is inefficient. It decreases eye-contact. It sounds written rather than sounding like speech, etc. We are the only department that teaches oral communication and therefore we need to insure that students are developing oral skills not merely vocalizing their writing skills. I was the one objector in the room.

My objection emerges from my experience. The extemporaneous (i.e., speaking from an outline rather than a manuscript) dogma is what I lived with as an undergraduate. At no point in either my undergraduate or graduate education was I ever taught how to write for oral communication. But, there is a need to learn to write for orality. The one I remember thinking about as an undergraduate was that of professional speech writing. But there are others situations where it is needed. Despite the potential for us to need to know how to write for oral communication, we were never taught it.

In Seminary at Brite Divinity School, the overwhelming bias--at least while I was there--was in favor of manuscript sermons. The reasons we gave for using a manuscript also make sense. When dealing with theological concepts we do not want to be sloppy with word choice. Also, a manuscript provides for better time management. I know to the minute how long a 3 page sermon will last but a half-page outline could be done in five minutes or take as long as an hour.

I adopted the manuscript practice. On many Sundays I read my sermon word-for-word from the pulpit. Starting around 2000, I started to memorize (more or less) my sermon manuscript and deliver the sermon with minimal notes. If I can run through the sermon three times before the first worship service, I can pretty accurately recreate the manuscript from memory. This stopped as my constant approach in about 2005 when my third child was born. The lack of sleep made it a lot more difficult. I've recently returned to my commitment to preach without a manuscript in front of me each Sunday. But whether preaching from a manuscript with me in the pulpit or preaching from memory and minimal notes, there has usually been a manuscript somewhere that I had prepared before preaching.

So, I had a dilemma. My speech com undergraduate education and teaching needs pushed for extemporaneous approach. My homiletics training preferred a manuscript. My speech teaching responsibilities asked me to give a lower grade to a practice that I myself habitually and intentionally engaged.

In part to relearn how to do extemporaneous speaking and in part to test out the competing claims about mode of delivery, I have made a personal decision to give--as best I can--every speech (sermon, report, homily) in an extemporaneous mode between now and the start of school. I will chronicle my experiences and draw conclusions based on what I learn.

Monday, April 23, 2012

Chuck Colson

Chuck Colson--the first man convicted and sentenced to serve prison time in the Watergate Scandal and the last to be released has died at age 80. At the height of his political power he described himself as Nixon’s “Hatchet Man.” He could be engaging, ruthless, conniving, insightful and power-hungry all at the same time. Yet, he had a tremendous fall from power. He participated in obstructing justice and seeking to cover-up the break-ins related to Daniel Ellsberg—a figure the Nixon Administration sought to dismantle both politically and personally.

Somewhere between his indictment and his trial, Colson had a conversion experience. A corporate executive he knew witnessed to him and gave him a copy of Mere Christianity. Through his seven-month prison experience, Colson developed strong opinions about the prison system and its inattention to actual rehabilitation. After his release, he began Prison Fellowship Ministries that works to bring the gospel and repentance to people serving in prison.

Colson was not without his critics. Many people doubted this “jailhouse conversion.” It was perceived as a public relations trick. Yet, for almost forty years—from the time of his conversion—he was not involved in another scandal. His Prison Fellowship Ministry is the largest of its kind, reaches those whom many regard as unreachable, and brings real and substantive change to people’s lives. The Prison Fellowship has served for over 30 years and made Colson one of the most influential people among American Evangelicals. He contributed significantly to Evangelical-Roman Catholic dialogue and cooperation—a stance that received significant opposition and criticism among those who failed to see the importance of Christian unity. In 1993 he received the Templeton Prize that is given annually to a person who makes a significant contribution in the spiritual dimension of human life. Shortly before I went to Seminary I read his 1994 book The Body. It is as helpful a work on the nature of the church as I have ever read.

As we consider the Minor Prophets and their call to repentance, Chuck Colson’s life stands near the top of the list of people who in recent memory so publicly and so profoundly displayed the power of repentance. Beyond the accomplishments and the prizes, Colson is testimony to the transforming power of grace. Thanks be to God.

Sunday, April 22, 2012

Two Tales of a City

Tale 1--In the 1980’s, Jerry Harvey made

the label “Abilene Paradox” popular within management circles. Stated simply,

the Abilene paradox is a group or organizational phenomenon where the members

of a decision making body perceive consensus where no real consensus actually

exists. Group members conform to this false perception of group consensus

without actually testing it or expressing their concerns. The definition, of

course, doesn’t do much to explain why it is called the Abilene paradox. For

that, you need the story.

Jerry Harvey had the good sense

to marry a woman from West Texas--Coleman to be precise. He and his wife

traveled home to be with his in-laws. The temperature was over a hundred

degrees. The wind had whipped up a mild sand storm. The visit was going well as

they played dominoes, drank lemonade, and enjoyed the relaxed comfort of a

small west Texas town. As it came to pass, one of his in-laws suggested that

they load up the unairconditioned Buick, circa 1958, drive to Abilene, and eat

at Furr’s cafeteria. Everyone said that it was a good idea. The family loaded

up, took US Hwy 84 north 52 miles and reached Abilene. There they ate at Furr’s

cafeteria. People go to cafeterias because everyone can get what they want.

Unfortunately, it all tastes the same and it never tastes like what people

really want. After eating, they drove back through the heat and dust in the

late model Buick in need of air conditioning.

Once back at the house, the

family members began one at a time disclosing that they did not really want to

go. They had only acquiesced to the journey because they felt that the other

family members had wanted to go. The conversation quickly dissolved into terse

responses and accusations. As Harvey relates, “After the outburst of

recrimination we all sat back in silence. Here we were, four reasonably

sensible people who, of our own volition, had just taken a 106-mile trip across

a godforsaken desert in a furnace-like temperature through a cloud-like dust

storm to eat unpalatable food at a hole-in-the-wale cafeteria in Abilene, when

none of us had really wanted to go. In fact, to be more accurate, we’d done

just the opposite of what we wanted to do.”

Now, that’s a much better definition of the Abilene

Paradox than the one I tried to construct before. It is memorable. So

memorable, people who have been exposed to the concept will sometimes be known

to speak up in the midst of decision-make meetings, “Are we on a trip to

Abilene?” The Abilene Paradox as a principle of management has been reproduced

in a book, a .pdf available on-line, and videos. It is Jerry Harvey’s calling

card as a management consultant weaving the principles of social psychology

together with leadership decision-making.

Tale 2--Twenty-two years after the

Abilene Paradox showed up in print, another writer for a very different field

narrated a very different trip to Abilene. In 2010 Lee Gutkind edited a series

of essays entitled Becoming a Doctor: From Students to Specialists,

Doctor-Writers Share Their Experiences. In this compelling set of reflections,

psychiatrist Elissa Ely has an entry entitled “Going to Abilene.”

She explains that she once

treated a paranoid schizophrenic who twice jumped off of a building obeying the

voices in his head. The act left the man restricted to a wheel chair and in

need of constant care. Unfortunately, the man’s paranoia made care-giving

exceedingly difficult. He would become violent when nurses tried to provide the

basic wound care and catheter maintenance that he needed to avoid infection.

The man lived in virtual isolation for many years. The man’s mother faithfully

visited even though he frequently directed his angry outbursts at her. She

would sit with the team of clinicians assigned to his care and ask questions

and discuss possible options.

In some desperation, the “Team”

decided to make the patient an actual member of their meetings when their

meetings involved his case. “Every Monday afternoon at 2 p.m., we would bring

him in for consultation” she explained. The sessions lasted about fifteen

minutes. At first, the man’s delusions dominated the conversations--his

pathological fear poured out in a torrent heartbreaking narratives--experiences

that were vivid in his mind but not in the actual confines of the hospital.

One afternoon the Team meeting

witnessed a break through. The man declared with a clear and authoritative

voice that he was headed to Abilene with 10,000 head of cattle. He wanted to

know if the Team members intended to accompany him. One by one, the Team

Members--the social worker, the physical therapist, head nurse, and

psychiatrist agreed. If he was going to Abilene, they were going with him.

From that point forward, the

man’s delusions took a turn. Rather than being the grim and destructive

delusions of the past, they became heroic. He saved the earth from a meteor

shower. He made huge donations to important charities. He owned sports teams.

He produced Hollywood films. As his delusions became more heroic, he became

more receptive to the care he needed.

Then one day it happened, the man acknowledged what

psychiatrists need their patients to acknowledge, “I know you think I’m nuts.”

He said. “You think I’m nuts but here’s the thing: there are ten of me in the

world--the politician, screenwriter, superhero. I can’t wait until they come

together in one man.” The shift in the man’s condition finally gave his mother

permission to age, as she should. With tears in her eyes, she rejoiced that she

could finally grow weaker as he grew strong.

Dr. Ely concludes her essay

saying, “If a man is ready to leave for Abilene, you must gather whatever pots

and pans and horses and tack and supplies you can lay hands on at a moment’s

notice and saddle up. The weak have grown strong; there is a miracle in the

midst of sickness. Sometimes, we are lead by our patients. Humbly. we follow.”

People who take either of these

tales seriously might use “going to Abilene” as short-hand ways of referencing

either story. For those influenced by Jerry Harvey’s “Abilene Paradox” taking a

trip to Abilene is a bad thing. If a group or company or nation takes a trip to

Abilene they will have failed to do what they wanted to do and the very thing

they have hated they will have done. For people influence by Ely’s Abilene

tale, “Going to Abilene” is a good thing. It is a reminder to those in the

healing profession that sometimes they need to participate with their patients’

own healing impulses and “humbly follow” the path that their own healing takes.

So, are you going to Abilene?

The easy way around this

question is to say, “It depends on which trip you mean.” We all want to avoid

acting foolishly, but we do want to act altruistically. Most of us could find

our way to justify either not taking the trip to Abilene or taking the trip to

Abilene. The two trips to Abilene each reveal something we hold true. By

coincidence they refer to the same place. I would suggest, though, that it is

not as easy for us to alternate between the two meanings of a trip to Abilene

at will. This has to do with the way figurative language works.

In figurative language we have a